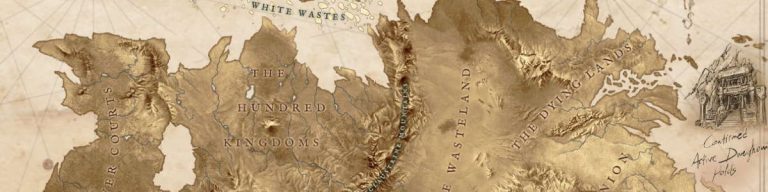

The cataclysmic Fall of Hazlia created a massive, dense haze of ash and dirt, plunging the world into an endless winter. In time, however, the black clouds that covered the world would be dispersed and, when light and warmth crept back into the world, it awoke nature from its century-long sleep. Enriched and strengthened by the raised dirt and ash of the Fall, the barren lands quickly gave way to lush fields and bountiful soil. This would contribute to the rapid expansion of the Hundred Kingdoms and the City States; as the Long Winter receded, these civilizations would have the space to expand in new and rich lands, capable of supporting an ever-growing population.

Doomed forever under the expansive rain shadow of the Claustrine Mountains, the Wastelands never benefited from this latent blessing. Bereft of rain and water, the barren dirt, rock, and sand of the gray and lifeless Wastelands would turn, at its lushest points, into a featureless scrubland, where only the most enduring flora and fauna could survive. This was the harsh land that housed all those of the W’adrhŭn tribes which had not secured a place in the lush oases created by the broken Spires. Eventually, however, these nomadic tribes would discover a hidden paradise; in time and with the rejuvenating power of the Fall’s aftermath, the lands east and south of the Abhoreth oasis, but still far enough from the dark Pyre whirlwind looming over Capitas, had exploded with life.

It serves, perhaps, as proof that nature works in cycles, that the fields which the W’adrhŭn were learning how to work had in fact been cultivated innumerable times in the past. The “new lands” of the nascent tribes used to constitute one of the lushest and richest areas of the Old Dominion: the Galtonni Province. Expanding in the west and north from the Spire of Abhoreth and the borders of the desert lands beyond, to the hills and mountains surrounding the Valley of Herm in the east and to the sea in the south, the Galtonni Province would become the richest region of the Old Dominion, save for Capitas itself. That stretch of land would once again been settled, this time by the former nomadic tribes of the Wastelands.

News about these lush lands spread fast among the roaming tribes and settlement began even faster. But the endeavor would prove neither easy nor peaceful. Generations of harsh living had developed a culture that tied raids and violence to survival, and this new paradise was too good a prize for any one tribe to claim. The wars that followed were as numerous as they were disastrous. As corners of this lush land were claimed and settled, the W’adrhŭn would come to realize that nothing in their culture had taught them how to exploit fertile lands. Their appetites and attitude would prove disastrous to the embryonic vegetation and, while these new lands were lush, they lacked in game. Adjusting their nomadic lifestyle to these new circumstances, a tribe would move into untouched land, drain it from all consumable resources, then move to another; and if that happened to be occupied, then war was the answer.

It is possible that eventually these tribes could have adapted further, possibly finding a balance with their surroundings, moving with the different seasons, and learning to allow the land to rest before returning to it. They were never given that opportunity.

When the Ukunfazane came to the new lands, she made the warring tribes an offer: learn to work the land or perish. Her travels among the humans had taught her the basics of agriculture and she offered this knowledge readily to those who were willing to listen. “Land-taming” they called it and its knowledge was given to the Bound, expanding their influence over the tribe and elevating their elder to a seat in the all-Tribe Councils. This shifting in power, however, was not taken kindly by all Chieftains. While most tribes accepted this new blessing by their goddess, there were those who resisted, continuing their nomadic wars, and raiding the settlers for their resources. The names of those chieftains have been forgotten and their tribes are collectively remembered today as the Poloatti Tribes – those who have been erased.

For the rest, however, life would change. Slowly but steadily, a new way of life would be developed – one that understood the value of settling, curating the soil, domesticating, and breeding animals for food. Soil filled with biomantic nutrients from the Spire oases would be brought to the new settlements in exchange for skins, plumes and meat from animals bred there. In time, rather than raiding and plundering, trading would become the dominant way of exchanging resources between the tribes. It was the beginning of a new way of life for the W’adrhŭn, one that promised the birth of a civilization which would rival those beyond the Wastelands. A civilization, however, that was doomed to die soon after its very inception.

To this day, few among the W’adrhŭn suspect why this dream had been allowed to bloom. Fewer still know for a fact that the strife and conflicts among the Anointed and the Fallen Pantheon moved in cycles and this brief period of prosperity simply coincided with yet another civil war among the ranks of the unGod’s servants. But once a semblance of balance had been achieved in Capitas once more, dead, coveting eyes would turn east once more, drawn by the opulent vibrance of life and the power of a Fallen Divinity would come to claim the land.

It began subtly. Crops that had every reason to be bountiful would start yielding less than expected. Animals would refuse to mate as often and stillborn cases became increasingly frequent among both the W’adrhŭn and their domesticated beasts. With time, things turned to worse. Entire fields withered and died for no discernible reason. Animals, especially young ones, died without an apparent cause. No signs of disease could be found among either the flora or the fauna; it was simply as if life was slipping away from them. Then, a hunting party that had ventured into the valley of the Great Turtle never returned. The search party that went looking for them shared the same fate. Only part of the warband that followed came back and they brought simple news: the dead had circled the Lost Oasis beyond the mountains. And they were coming.

The war that followed was intense and gave birth to many tales of heroism and victory for the W’adrhŭn. But it was ultimately futile. It would not be long until it became apparent that the land could no longer support the settlements and the war was being fought for dead land. The tribes would once more pack their things and forge caravans, returning to the Wastelands and the harsh nomadic life of their ancestors. Quietly, softly, the W’adrhŭn dream of a new way of life would wither and fade with the crops and animals that had inspired it. Unlike them, however, this dream would never truly die. Remembered in songs and tales exchanged around the fires during the cold, wasteland nights, the roaming tribes would remember the time when they tamed the hardest beast, the land itself; the time when the fields would stretch lush, green and colorful around them.

To this day, the memory of the Lost Land lingers among the W’adrhŭn – as does the memory of the foe that stole them. There could never be peace between the living and the dead; but even if it could, the W’adrhŭn would not accept it.